BY FRANK GREEN

Times-Dispatch Staff Writer

Sunday, April 2, 2000

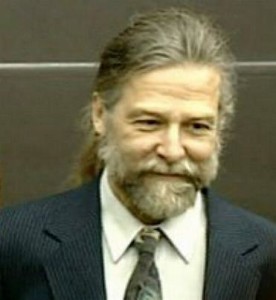

RICHMOND, Ill. — Gary A. Gauger is an organic vegetable grower, his life in sync with the rhythm of the seasons on 10 acres of farmland and hardwoods just off Highway 173 near the Wisconsin state line.

He grows his crops, tends his goats, tinkers with tractors and minds his own business. It’s hard to imagine the bearded, plain-spoken, 48-year-old teetotaler is the criminal justice system’s worst nightmare.

In January 1994, Gauger was sentenced to death for cutting the throats of his elderly parents. Now exonerated, he is one of 13 former Illinois death-row inmates whose wrongful convictions have triggered a national debate on the death penalty and prompted a moratorium on executions in Illinois.

Eighty-seven men and women have been freed from death rows across the country since 1973, but the debate has largely been ignored in Virginia.

In Virginia, 76 death-row inmates have been executed since 1976 — but none have been found to be wrongfully convicted.

The stories of the 13 freed in Illinois have become potent arguments for opponents of capital punishment. Each offers a lesson in the shortcomings of the legal system — lessons Virginia ignores at its peril, opponents warn.

Interviewed at his kitchen table last month, Gauger said his nightmare started on the morning of April 9, 1993, when a customer showed up on what was then the 214-acre farm of Morris and Ruth Gauger in northern Illinois. Gary, 41 at the time and a recovering alcoholic, lived with his parents.

The customer was looking for a motorcycle part. Morris Gauger repaired motorcycles in a garage behind their farmhouse.

It was a Friday, and Gary had not seen his parents since Wednesday night. He thought they’d gone on a trip. He found his father in the back

room of the garage face down in a pool of blood. “I thought he’d had a stroke or heart attack, fallen down and hit his head,” the son said. He called the rescue squad.

But when the rescue workers arrived, they quickly called the McHenry County Sheriff’s Department.

Investigators told him they suspected foul play. “They didn’t elaborate. They were looking for my mother around the farm.”

They found her in a small trailer on the property where the family sold Indian rugs.

Morris Gauger, 74, and his wife, Ruth, 70, had been bludgeoned to death, their throats cut. Morris’ body was covered by an overcoat; Ruth’s was rolled up in a piece of carpet.

After Ruth Gauger’s body was found, Gary Gauger was immediately frisked and locked in a squad car, he said.

“I told the police everything I know,” he recalled. “They showed up between 11 and noon. I sat in the squad car until 4 [p.m.] They took me to the police station in Woodstock, the county seat. And I was questioned from 4 o’clock until 10 o’clock the next morning.”

According to news media accounts, detectives said Gauger confessed and told them: “I don’t know why I did this,” adding that he was “in a fog” when it happened.

Gauger denies confessing. “As soon as I found my father’s body, it’s like I stepped into a dream world. Here’s my dad, dead. The police show up right away. My mother’s missing. I haven’t got a clue what’s going on and I’m locked in a squad car.

“By 3 o’clock that morning in the interrogation office, they’re telling me they have a stack of evidence against me. . . . They said I had failed the polygraph. They said my body couldn’t lie.

“They were basically trying to convince me that I killed my parents and, for a while, through lack of sleep, incessant interrogation, not being really able to think on my own for 10 seconds at a time, they had me believing that I must have had a blackout and that I killed my parents.

“They assured me this happens all the time,” he said. “It was not whether or not I killed my parents, it was why. They knew I did it.”

He was tried and convicted, the most damning evidence his alleged confession. On Jan. 11, 1994, Gary Gauger was sentenced to death.

Prosecutor Phillip Prossnitz told Judge Henry Cowlin: “He killed his own parents. He killed the woman who brought him into this world. . . . The jury believed the testimony of sheriff’s detectives about how Gary Gauger confessed. He confessed in great detail.”

According to a newspaper account of the trial, Prossnitz said: “It is unimaginable the pain his parents must have suffered when their throats were slit, almost from ear to ear.”

Less than a year later, Cowlin reduced the sentence to life because of Gauger’s minimal prior criminal record and mitigating factors such as admitted longtime marijuana and alcohol use.

The judge took the action over the strong objections of prosecutors.

Then, in March 1996, the Illinois Appellate Court ruled that Gauger’s confession should not have been used against him. The appeals court said it was improperly obtained because McHenry County authorities had no probable cause for holding Gauger some 21 hours after the bodies were found.

He was freed from the maximum-security Stateville Correctional Center in October 1996. But he was cleared on what many called a technicality, and a cloud of suspicion hung over Gauger’s head. His brother, Greg, harbored doubts.

And the real killers were laughing at the joke they had pulled on Gauger.

. . .

Thirteen condemned men have been freed from Illinois’ death row in recent years. Many of them can credit David Protess, a Northwestern University journalism professor, and his students for their change in fortunes.

“I am not a cop basher,” Protess said. “I respect tremendously what law enforcement and prosecutors do, and the vast majority of times they get the right person.”

Yet, he said, they can — and do — make mistakes, and innocent people end up on death row.

“It’s a national problem,” Protess said recently over lunch at an Oak Park, Ill., restaurant near his home.

Protess said such exonerations face obstacles in some states, including Virginia, because of the difficulty in getting newly discovered evidence into court and strictly applied procedural rules. “We couldn’t do effectively in Virginia what we do in Illinois.”

Protess and his students investigate cases by poring through old records, interviewing witnesses and pursuing other suspects. Sometimes they conclude the killer is guilty, sometimes that the killer is innocent and sometimes the students cannot reach a conclusion, he said.

In Illinois, there is no time limit on introducing new evidence of innocence in death cases, Protess said. “That’s one reason why we’re so successful.”

But in Virginia, once 21 days have passed after sentencing, a new trial cannot be ordered because of the discovery of new evidence, even DNA evidence. A court can order a new trial if it finds a constitutional rights violation occurred, based at least in part on newly discovered evidence. As practical matter, such a rights-violation claim must be made within a year of sentencing.

An effort to loosen the 21-day requirement to three years failed in the most recent General Assembly session. Opponents are concerned that loosening the limit would open cases up to frivolous appeals and delays.

“Are there innocent people [on death row] in Virginia?” Protess said. “There’s no question in my mind about it.”

But Virginia Gov. Jim Gilmore, a former Henrico County commonwealth’s attorney, disagreed.

“There isn’t a need in Virginia” to study whether there are adequate safeguards against sentencing the innocent to death, said Mark Miner, a Gilmore spokesman.

“The governor has confidence in the judicial system as it is right now,” Miner said. “When there’s a clemency petition filed, he personally looks in to each case on an individual basis, so there are precautions in place.”

Gilmore, the spokesman said, has no concerns the state might have executed an innocent person or that it might happen in the future. Each case goes through multiple layers of state and appeals courts to ensure the conviction and sentence were proper, he said.

Kent Willis, executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union of Virginia, said Gilmore is wrong.

“Every state in the union [with capital punishment] has some flaws in the way it carries out the death penalty,” Willis said. “Virginia, though, may be the worst of all.

“Every significant obstacle to justice is present, including inadequate trial representation, racism, blindly aggressive state attorneys and courts that fail to properly review cases on appeal. Indeed, the Virginia Supreme Court has the lowest reversal rate [of death cases] in the nation.”

Gilmore’s counterpart in Illinois, Republican Gov. George H. Ryan, no longer has the confidence in the Illinois system that Gilmore has in Virginia’s. On Jan. 31, he announced a moratorium on executions so that the system could be studied in light of the 13 wrongful death sentences.

Protess is not surprised at the national attention on Illinois’ wrongful convictions and on Ryan’s decision.

Among other things, a Gallup Poll in February showed support for capital punishment was at its lowest level in 19 years, with 66 percent of those polled favoring it.

Bills have been introduced in both the U.S. Senate and House that would help prevent innocent people from being sentenced to death, Pennsylvania is considering a moratorium, the New Hampshire House of Representatives voted to abolish the death penalty and Indiana Gov. Frank O’Bannon has called for a one-year moratorium on executions to ensure there are adequate safeguards against executing the innocent in that state.

Protess attributed much of the furor to the fact that Ryan is “a conservative Republican governor who is pro-capital punishment. I think that if it had just been a liberal, Democratic governor who just had questions about the death penalty in Illinois . . . it probably wouldn’t have had the national ramifications that it’s had.”

Protess is glad for the attention.

“I’m delighted that our country is finally debating one of the most serious questions about life or death and that journalists are beginning to cover capital punishment again,” he said.

“Journalists have focused so much on violent crime that politicians have found the death penalty to be a quick-fix solution that makes them look good. At the same time, journalists have not looked at the innocence of death-row prisoners.”

Northwestern University now has opened a legal center called the Center for Wrongful Convictions, created by Northwestern University School of Law professor Lawrence C. Marshall. Marshall has played key roles in freeing some of the wrongfully convicted inmates.

The center puts together the investigative work of Protess’ students with the legal work of Marshall’s students.

“One of the reasons Illinois is getting so much attention is [that] it’s outsiders like my college students who are helping to make the difference — and that made it newsworthy,” Protess said.

“Some people would consider that inspiring,” he added. But, “I think it’s appalling.”

. . .

When word of Gauger’s arrest in the slaying of his parents got out, members of the Outlaws motorcycle gang thought it was pretty funny, member James Schneider later confessed.

“We said we could write a book about how to do the perfect murder and not get caught because the son had admitted to it,” Schneider said, according to news media accounts.

The gang believed the Gaugers had stashed cash at their motorcycle shop. Two members went to the farm in April 1993 and killed the Gaugers during a robbery. The killers used the $15 they stole to buy breakfast.

From his vantage on death row, Gauger could only imagine who might have really killed his parents.

Living under a death sentence, Gauger said, meant “I was scared a lot.”

“I thought about it a lot. There was nothing I could do. It was totally out of my hands,” he said. “If they took it to its final conclusion and killed me, there wasn’t really anything I could do about it. I had accepted that.”

Then his sentence was changed to life, and rather than dwelling on the possibility of being executed, he had plenty of time to consider who really killed his parents.

His twin sister, Ginger Blossom, and her husband had moved into the two-story, frame farmhouse where his parents had lived.

His twin sister, Ginger Blossom, and her husband had moved into the two-story, frame farmhouse where his parents had lived.

“The crime was never really investigated,” Gauger said. “I was very concerned about my sister and her husband living at the house there because we didn’t know why they had been killed. There was a theory that my parents had been approached by developers who wanted to develop the farm and dad had told them off to a point maybe they’d gotten so pissed off they arranged to have him killed.

“My dad had had to fire a guy because of alcoholism. Worked for him 15 or 20 years. He could have done it. There was a theory the Outlaws had approached my parents and tried to get them to sell stolen motorcycles through containers and ship them overseas.”

The last theory was closest to the truth.

It was not until after Gauger had been released from prison that he learned what happened. Federal authorities, who had been investigating the criminal activities of a motorcycle gang, came across the real killers.

In June 1997, a racketeering indictment against 17 members of the Outlaws motorcycle gang was made public. It alleges the gang committed six murders — including those of the Gaugers — and other crimes.

The trial is under way in Milwaukee.

Meanwhile, Blossom lives in her parents’ home. From the beginning, she never doubted her brother’s innocence. When she learned he had been charged, she couldn’t believe it.

“I was totally incredulous,” she said. “It wasn’t possible. It was absurd. But again, the whole thing was kind of surreal, that your parents had been murdered.

“People who knew him knew that Gary couldn’t do anything like that. He might have had silent supporters, but nobody really came out [to support him] until he really was exonerated.”

Gary now lives on the 10-acre property adjacent to the farm that his parents bought in the 1980s. In October, he filed a federal lawsuit against officials in the McHenry County Sheriff’s Department and the state’s attorney’s office.

Interviewed in his small farmhouse, Gauger said: “I’m a certified, organic vegetable farmer. We have a stand next door, a gazebo in front of the house, and we also do four farmers markets,” he said.

“We do some 15 varieties of tomatoes, 15 varieties of sweet corn, probably that many variety of peppers. It’s all for the fresh retail trade, so we do a lot of variety in small quantities.”

Gauger is able-bodied and can handle the rigors of farming. His psyche, though, remains scarred.

One recent Saturday, when the sun beat warm and welcoming on the land, he stepped outside and admired the weather.

“It’s sunny,” he said. “Makes things grow.”